BEING AUTISTIC: An Interview with Emma Van der Klift

NORM: Emma, over the past few years you’ve recognized that you are autistic, and in the last year you actually received a diagnosis. Now, I know when people meet you, and for many people who have known you a long time, they are often surprised and maybe even bewildered by this. So I’m going to ask the questions that people may have in their minds but might be afraid to ask. And I’m going to ask you some additional questions that others may not have thought of but come up because I know you so well.

EMMA: Great. Let’s go.

NORM: Before we get into how you came to understand yourself as autistic, let me first ask what people might be thinking about the way you come across. I’m sure people wonder “how is it that you can be autistic when you are social, you make eye contact, you understand humour and you have empathy”? Not only that, you have a successful career, a graduate degree, you’re a mediator and a negotiator, you’re married and you have children? These are things that people generally assume are impossible for autistic people. Could you comment on that?

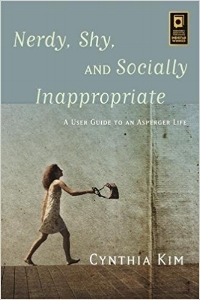

EMMA: Whoa that’s a lot! Let’s take that apart and address those issues separately. First, it’s important to address a few commonly held stereotypical ideas of what autism is. So many of the stereotypes and ideas out there are based on how little boys show up. One of the jokes we make in the autistic community is that the benchmark stereotype we all get judged by is whether we look and act like an 8 year old white boy who loves trains, lines up their toys, and is in a perpetual state of meltdown. For the longest time, I bought into those ideas too, which was why I didn’t recognize myself as Autistic until I began reading the work of Autistic women (as in Cynthia Kim's book, "Nerdy, Shy, and Socially Inappropriate) and began to see how differently Autistic girls and women can show up. In general, girls and women are underrepresented in the literature on autism and there’s very little research on how those differences might play out. (And by the way, just for the record, I actually did used to line up my toys, I do love trains, and as you know, I am subject to meltdowns from time to time...so there is that...)

So that’s the first piece that actually sets up the rest of your question. As for being social, as you well know, I am actually an introvert in disguise. I can emulate extraversion on occasion, but it’s quite taxing. The commonly held definition of an extravert is someone who gets energy from being around others. I don’t! As you know, I generally need an inordinate amount of down time after any social event. And that’s not just conferences or parties, but even one to one conversations. And we’re not talking about a small amount of downtime, either! It can be hours or it can be days. I tend to pay a pretty heavy price for being social, but I’ve always pushed myself to do it, because it seems expected. Until quite recently, I actually thought most people worked that hard! And I really want to add here that none of this means I don’t like people. I do!

Next, eye contact. Yes, I can make eye contact. I was rigorously schooled by my father on that from the earliest age. He believed, as many people in western culture do, that eye contact is a sign of respect. So he’d line my sisters and me up and make us look him in the eye. However, like a lot of autistic people, I can fake eye contact, too. If I look at the bridge of your nose or your mouth while you’re talking, I bet you wouldn’t even notice!

Then there’s humour. Yes, I do understand humour, irony, metaphor and some other things that autistic people are generally believed not to be good at. In fact, most of the autistic adults I know have a finely tuned sense of humour, and certainly understand irony! That said, I’ve learned a lot about conventional neurotypical humour over time, and much of it I’ve learned through mimicry, reading, practice and coaching. I didn’t always understand it as well, though. As a younger person I had a lot of trouble understanding whether someone was trying to be funny or if something was meant literally. It was actually quite embarrassing. There was that terrible moment when I actually thought a jackalope might be a real thing…well, we won’t get into that. When I was first dating, I had a friend who made it her mission in life to help me decode things. She’d hear some guy say something to me, and she would pull me aside and say “Emma, that’s a line!” My misunderstanding of humour and social cues actually put me in some potentially (and some actually) dangerous situations as a young person.

And as for empathy, don’t get me started! This is the biggest misconception about autistic people, and it really annoys us. In fact, many, if not most autistic people will tell you we don’t lack empathy, but in fact experience hyper-empathy. Unfortunately, hyper-empathy is really exhausting. When you are processing your own feelings, to have the feelings of everyone else in the room pushing in on you is quite overwhelming. All my life I’ve struggled to understand boundaries. It’s like I’m not really sure where I leave off and you begin. It’s probably a big factor in why social events are so draining for so many of us.

NORM: I know in my training as a family therapist, the awareness of personal boundaries was central. I used to bring up the importance of setting boundaries when we first met, and I know that this was both mystifying and upsetting to you, and in some instances created some conflict between us. Could you talk about that?

EMMA: As I mentioned earlier, boundaries have always posed problems for me – mostly because I can’t figure out where they are. This results in misunderstanding and sometimes fairly huge social gaffes. I either talk too much or I can’t talk at all. I often hijack conversations to a place that I’m interested in or comfortable with. And I don’t always notice when other people are tuning out. I’m getting better at looking for the cues that people give, but I’m not sure this will ever be easy for me.

NORM: Many people assume that autistic individuals are rigid and become distraught with any change in routine. I already actually know the answer to this, but could you elaborate?

EMMA: Haha! In my case they might not be wrong! I am not exactly spontaneous. I need to know what’s going to happen next and I can get – as you know – quite terribly insistent and repetitive about it. Your support is always incredibly helpful to me – you are endlessly patient in explaining the same trajectory of events over and over to me. It’s anxiety, and a need to predict and to have a sense of control. Part of it is because people are still unpredictable to me, even at this point in my life, and I never know what’s expected of me. The more I can visualize what’s going to happen in a step-by-step way, the better I’m able to cope.

NORM: So let’s talk about the second half of my earlier question. I’m sure a lot of people would feel skeptical about your diagnosis merely because you have a successful career, a graduate degree, you’re a mediator and a negotiator, and that you’re married and you have children.

EMMA: First of all, let me assure you that a lot of Autistic people have successful careers and hold multiple graduate degrees. Some people teach in universities, others are engineers, software designers, lawyers etc. And many Autistic people are married and have children, as well. With respect to my career as a speaker, sometimes people ask me how it is I can stand in front of audiences and deliver speeches even though I have fairly severe social anxiety. Well, there are a few things at play. First, when I’m at the front of the room, there’s like an invisible line between me and the audience that makes talking easier. It’s not like a party or an unstructured event where I have to make small talk, which is very hard for me. Also, the topics I present on are all connected with something that has been one of my longest standing passions – social justice. And finally, I’m not ashamed to say that most of my presentations are scripted. Much of my social interaction is fairly scripted, too. This isn’t because I particularly want to impress anyone, or fool them, but simply because it helps me manage my anxiety and gives me time to think about what words I want to use and construct them in ways I think people will understand. I admire people who can present extemporaneously and answer questions on the fly. I am not one of them.

As for my graduate degree? Yes. I do have a Master’s Degree. But what most people don’t know is that I didn’t finish highschool, and I only have part of an undergrad degree. Most school was incompatible with my learning style. Once I got to grad school, though, I knew what I wanted to do and managed to soldier through. I was also given a lot of latitude because my instructors seemed to enjoy what they saw as my quirky way of approaching issues. Having supportive instructors meant the difference between needing to leave yet another educational institution and not only surviving it, but being appreciated for my contribution.

Yes, I’m a certified mediator and negotiator. I was really drawn to communication from early adulthood on, and it fit with my social justice ideals as well. But in retrospect I think I chose that field because it offered me an unusual opportunity to learn social skills. It wasn’t a conscious choice. On some level I think I gravitated there because I sensed that there were things to learn that would be helpful for me. So much attention is paid to interaction in both mediation and negotiation, and that allowed me to learn things about body language, communication styles, how to decipher intent and basic interaction in a pretty formalized step-by-step kind of way. As an aside, a lot of autistic people find unusual and unexpected ways to learn social skills! As I became a coach for budding mediators and negotiators, I was able to put that into long term memory – kind of like learning a sport or some kind of exercise. Like putting something into body memory. And teaching, as you know, is the best way to cement learning. Karla McLaren, in a really interesting thesis, explored with autistic adults how some have had unusual trajectories into social skills learning that they uncovered on their own outside traditional therapies. It’s not uncommon. And this was mine.

So what about the “married with children part”? Well, you and I have been married for 25 years now, and together for almost 27, but I was married twice before that. Both of my ex-husbands are neurotypical men, and with all due respect to both of them, they had a hard time understanding me, as I did them. So there was a lot of cross-cultural misunderstanding you could say. You and I often joke that we didn’t fall in love so much as fall in recognition. You are pretty neurodivergent yourself, and I think that’s why it works so well for us. Among autistic people, like many people with Cerebral Palsy, you’re considered an “autistic cousin”. You and I have never engaged in mutual remediation, we have always practiced acceptance in our relationship, and even written about that. Everyone does what they do best, we’ve always said. Interestingly, I think you’d agree that our relationship has even gotten better since my diagnosis.

NORM: Do you see similarities between your experience and my experience with cerebral palsy?

EMMA: I do. I think your neurodivergent brain is a bit like mine – you focus with intensity and you see patterns. Also, you’ve often talked about living in a body with a mind of its own, something that many autistic people can relate to. In fact, I was surprised to see a young autistic writer, Ido Kadar, use the same phrase to characterise his experience.

NORM: And finally, the last part of my earlier question. What about the fact that you have successful grown up children?

EMMA: And finally, yes, I do have successful grown up children. J They are absolutely amazing people! I’m very proud. Now, when they were growing up, they had a certain amount of weirdness to cope with – I’m a very visual person, and everywhere we’ve ever lived has reflected that. Some of the environments were strange installations and were considered quite peculiar by their friends! As a parent, I also needed a lot of help, and time away from them in order to cope with all the intense inter-personal interaction that comes with childhood and parenthood. But luckily, I had that help, and we have always done well together. They are quite forgiving of my so-called quirkiness and my bottomless obsessions! Also, I think they benefitted from growing up in an accepting household where remediation wasn’t on the menu, and where they were allowed and encouraged to pursue their interests. We’ve always said that we were a “parallel play” household!

NORM: Looking back, how did your family respond to what you would now consider your neurodivergence?

EMMA: My family was actually pretty wonderful and pretty accepting. We are all three – my sisters and me - neurodivergent in our own ways, so I guess our parents didn’t have anyone to compare us to. As children, we were encouraged to read, do art, and the fact that we spent entire days either in our rooms alone or in the forest, at the river or hanging out with horses and other animals was never questioned. We were not subjected to the kind of hyper vigilance that many kids are subjected to today. I know I was sometimes quite irritating with my single-minded focus on whatever my current interests were, but it was usually received with good humour and maybe a bit of head shaking. I was never punished for it and it was never suggested that I should be some other way. School was the place where I really came to understand that I was different, and that difference wasn’t always a good thing. The idiosyncrasies that my family accepted were transformed into that teacher litany of disappointment. Could try harder, must do better. My mother, although we never talked about this, colluded with me. When I was overwhelmed (which was often) she would let me stay home in bed and read. She’d bring me soup and not require me to talk. I’ve looked at report cards from those early years, and some years I was out of school as much as 45 days.

But as I became an adolescent, things got harder. School got even more difficult for me, and I had a lot of things to figure out about social relationships. I kept running away. Many years later my mother told me that our family doctor recommended that she tie me to the bed to keep me home. She was appalled, and of course never did that. As an adolescent, my interest in social justice issues really blossomed – anti war protests, anti nuclear protests, etc. My family called me the crusader – something I didn’t like for all kinds of reasons that I’m sure you can imagine. But still, they were accepting.

NORM: You just said school was difficult. I’d like to go a bit deeper. Could you talk about your experience at school?

EMMA: Sure. My issues really didn’t come up in any observable way until school. Again, I think that this was because my family just accepted me with all my quirks. However, once I got to school it was a different story. The classroom was a difficult place for me – fluorescent lights, noise, and a combination of work I found difficult and work I found ridiculously easy. So school was a process of ricocheting between boredom and anxiety. I was a hyperlexic kid, I could read in 2 languages by about the age of 3, and consistently read many years above my age group. But I was, and continue to be very dyscalculiac. This made the teachers quite confused. So they knew I was smart, because of the reading, and surmised that all my other issues were just moral failings. I wasn’t trying hard enough, I didn’t pay attention etc. By junior highschool I’d about given up, and my behaviour got quite difficult. I quit school at age 15, left home, joined a cult, dabbled in witchcraft. But those are other stories for another time!

NORM: Did you have friends in school?

EMMA: Mostly the other loners and outcasts. I didn’t have many friends – today I don’t know anyone from my school days. Like a lot of autistic kids, my way of trying to learn social behaviour was through mimicry. I’d fixate on one kid and study them like a beetle on the end of a pin. I’d actually try to “be” them, like I did with one particular girl in middle school. I even wrote her name on my rulers and in my exercise books. This, needless to say, made me seem pretty strange as it didn’t go unnoticed! In high school I had one friend, and I did the same with her. It wasn’t always easy for me to connect with the other kids, since I had a stilted way of talking and had a huge vocabulary that made me look like I was trying to show off or was snobby. The other kids called me (and my sisters) “the walking dictionary”, and it wasn’t a compliment. Because I didn’t really understand why the other kids did the things they did, I felt like the proverbial deer caught in the headlights, always a bit stunned. I read more than I related to people. I spent an entire year talking in what I thought was a Cockney accent because of a series of English books I was reading and movies like Mary Poppins and Pollyanna that I was watching. This further singled me out as strange. As a result, I kept to myself and didn’t share much. Even as an adult, friends would say to me “we tell you everything, and you never tell us anything about yourself”. I really wasn’t sure what they wanted to know, and the obsession with self-disclosure seemed a bit boring to me. Which is ironic, given this interview and everything I’m telling you!

NORM; You started working with disabled people as a young adult.

EMMA: Yes. At 19 I went to work in a group home for ten people. We actually thought that a group home that size was “state of the art” back in the 70’s! I was the same age as the people I was working with – my job was called “supervisor”, which is really a pretty terrible job title. But because we were all the same age, we did the same things 19 and 20 year olds do – we had water fights, we went to the bar, we stayed up too late watching movies, we went to the beach, took trips to the city and ate badly. None of this was what “supervisors” were supposed to do! But we figured if nobody asked, we didn’t have to tell them. Some of those people are still my friends, even though we live in different communities now.

But the thing is, I had an immediate sense of connection – especially to other Autistic people. For some reason, I felt very profoundly that these were my people! I spent most of my “off time” with them, not just my work time.

My entire adult life has been centred around disability issues, and in the context of what I now know about myself, this makes sense. I gravitated towards disabled (and especially autistic) people starting in my teen years, and actually even before that. I have early memories (I was maybe 5) of a man in our neighbourhood who was ostracized and feared because he was seen as “odd”. None of the children, including my sisters, would go anywhere near him. He and I, on the other hand, had an immediate connection. We would sit on the stoop in front of his house and talk. Once I remember he took me into his house – something that would never happen between an adult man and a 5 year old girl today - and told me he’d worked on the railroad all his life and had collected all the buttons people had lost. He had jars and jars of them lined up on all the open shelves in his house! Today he’d probably be considered a hoarder. To me, his collection was fascinating. When I look back I understand our immediate affinity. We just “got” each other.

I have always had a real sense of belonging and relatedness with disabled people that I didn’t fully understand until fairly recently. So that’s another piece that fits with the career question. I’ve only ever had jobs where I worked with disabled people. It seemed to be kind of an inevitable choice.

And really, before we figured out that I’m Autistic, even you used to say I was an autism magnet. For quite a few years we would go to Syracuse University where Doug Biklen was doing important work with Autistic people and communication. Every time we were there I would have the same weird sense of relatedness, and people would have it towards me as well, even though most of the people there seemed on the surface to be very different from me. Most used AAC devices and didn’t speak. I had no way to figure out why I felt so connected, and again, that relates back to the images and ideas about autism that I’d actually bought into that were false.

NORM: From my experience as your husband, what I’m aware of is your hyper-sensory awareness. Whether it be fluorescent lights or bright light in general, loud noises, tactile sensitivity... what I’m aware of is when I encounter loud sirens or fluorescent lights, I have the ability to block it out, whereas it seems that you can’t do this. Could you comment on that? Can you give us a sense of what it’s like to not be able to filter it out?

EMMA: It took me a long time to understand that everyone didn’t experience the world like I do. Fluorescents, and actually any overhead lighting, and even bright light outdoors are quite excruciating. I’m wearing blue tinted glasses these days, and that really helps. The yellow ones that everyone seems to think are an antidote for fluorescents just don’t work for me! I’ve always been sensitive to loud noises and have a pronounced startle reflex that even seems to be intensifying as I age. Oh well.

When you talk about filtering, I think about the differences we have in navigating public spaces like restaurants. You say you’re able to filter out the conversations going on at adjacent tables, while I can’t. I just hear them all. And you’re always surprised when I can hear things in another room – like when the printer turns on in the office, when the neighbour’s dog is barking or when the neighbours above us forget to turn off the fan in their bathroom and I can’t sleep as a result. It’s interesting. I’ve actually tested as hard of hearing in my left ear, and I have persistent loud tinnitus, but it doesn’t change that issue. I’d love to see some research on this, because my sense is that it’s not so much a hearing thing as a brain thing.

One of the good things I’ve figured out is in this society these days, is that it’s OK to wear noise cancelling headphones. You don’t even look out of place anymore! Also my sense of smell and my sense of taste are quite pronounced. An example? My sister and I were in a store recently, and when we got to the cashier, my sister – who is also sensitive this way - said “I don’t know how you can work next to all those plastic bags! They smell horrible.” We nodded to each other, while the cashier looked confused.

NORM: I know that when we go to a restaurant and taste a dish, you can figure out what’s in it and then replicate it at home. I guess that’s about your sense of taste.

EMMA: Ha! It’s my autistic superpower! (And it’s also one of my passions) Just one more thing about sensitivities, although I’m quite sensitive to all these things, I’m also paradoxically a sensory seeker. Especially around things like food – I love intense flavours, heat, spice etc. And sometimes I like loud music. And certainly I am a visual sensory seeker. Less in the visual range is not more for me – more is more! And this confusing dichotomy is true for lots of Autistic people, I’ve discovered. Sensory seeking and sensory avoiding.

NORM: What about tactile sensitivity?

EMMA: Yes, like many autistics, I am quite touch resistant. I can hug people, if they are tight pressure hugs, but light touch is enough to make me want to jump out of my skin! Also many textures are problematic. I could never have been a teacher because I can’t bear the feeling of dry chalk. I was never a good gardener, because I can’t stand the feeling of dry dirt on my hands. Even thinking about dry potatoes sends me into a tailspin! Cold velvet on the back of my fingernails…well, it would be hard to explain!

NORM: People have said “you can’t be autistic, because you don’t stim”. Is this true?

EMMA: Ha ha! I have always stimmed. One of my earliest memories is telling my mother about my favourite stim, rubbing my fingers together in a particular way that engenders very intense feelings. She told me I’d get hangnails. She was right, but all these decades later it’s still my go-to stim. I have even caught myself waking up in the middle of the night stimming on my fingers! I remember asking you once what you felt when you did this – and you looked at me with this perplexed expression and said “um, skin on skin?”. I had no idea other people didn’t necessarily feel the intensity of what I felt.

I also finger spell in the air, and often move air around in my mouth in ways that are impossible to describe adequately. When I’m alone, these stims are quite obvious, but like a lot of autistic people, I’ve learned to dial them down because they aren’t socially acceptable. So as a result, many of my stims are quite subtle, but some are not. These days I feel free to use stim toys to self-regulate as needed. Even in public. I tend to favour neon coloured slinkies these days, fidget spinners (the best invention!) or twist toys.

I used to try to hold myself still during presentations on stage. These days I’ve given myself permission to do what I need to do – move around, pace, carry stim toys. That’s one of the perks of coming out of the Autistic closet – you get to let your freak flag fly!

NORM: So I know, being your husband of 27 years, that in the past you’ve devoted a huge amount of energy trying to appear what we might call neurotypical. Could you talk about what that means?

EMMA: Passing, you mean. Yes I have expended an enormous amount of energy on passing, but that was mostly before I recognized myself as Autistic. In some ways I didn’t even know that’s what I was doing. I just knew that there were parts of me I wanted to hold in check because I didn’t think they’d be socially acceptable. And there were certainly parts of my past and my childhood that I didn’t want to share, because I believed they made me look less credible. Career limiting disclosures, right? Like the fact that I didn’t finish high school…

I’m getting older now, and passing is becoming more difficult. I don’t have the energy for it that I used to have. And, to be truthful, now that I’ve acknowledged that my “modus operendi” in the world has been characterized by passing, it makes me feel like a coward. Every hour I spend covering up my idiosyncrasies and my neurodivergence is an hour where I deny my neurodivergent sisters and brothers. It’s an hour where I say with my actions “It’s better to be neurotypical. It’s better to pretend I belong with the cool kids”. And when I do this, I’m engaged in the unsavoury practice of throwing my Autistic and otherwise disabled peers who do not have the luxury of passing, under the proverbial bus.

These days I’m learning to let myself be myself. To ask for accommodations, to stim in public. It’s very freeing. Jane Strauss, in a chapter in a wonderful book called “All the Weight of Our Dreams: On Racialized Autism” talks about another use of the word passing which relates to death. When we talk about death, we often say that someone has “passed”. Jane says that passing is a kind of death, and I would agree. It erases difference (which erases people) and it is a kind of soul killing denial. And it’s exhausting!

NORM: I know that one of your concerns is that in asking for accommodations you will be seen as entitled, or a princess. Could you comment on that?

EMMA: Yes, that is a concern. In the past I never asked for any kind of accommodation. I worked in hostile environments with loud sounds, fluorescent lights, and a lack of down time, and I just suffered through. Sometimes I could make my own accommodations – like bringing in lamps for ambient light so that I could turn off the fluorescents. But it never occurred to me that I could actually ask for anything. I thought it would be rude. And really, I kind of thought that everybody was soldiering through the same things. I’m learning to ask for things now. It’s freeing and at the same time anxiety provoking.

NORM: I’d like to talk about something that we hear a lot about when people talk about autistic characteristics, and that’s “special interests” or obsessions. Both of those words are quite denigrating, actually. The one thing that I know is true for both of us is that when we get excited about a certain topic or activity, we usually become obsessed with it!

EMMA: Our mutual friend, the late Herb Lovett, once said “anything worth doing is worth doing obsessively”! I couldn’t agree more. And really, I think our so-called obsessions – like social justice, chess, art, writing etc are what make life worth living. I can’t imagine life without books, anagrams, crossword puzzles, chess, movies and art!

The way we operate together is often a lot like a little think tank. Because we share the tendency to delve deeply into what interests us, and the fact that many of those things coincide, is the most amazingly wonderful happy accident. We don’t remediate each other, we are synergistic.

NORM: In our lives that’s a source of real bliss and connection and intimacy. and yet, many clinicians and some parents believe that what they call “obsessive tendencies” should be eradicated or at least diminished. Could you comment on that?

EMMA: I think that’s tragic! Those intense interests are about bliss, and they are also about learning. Many of the things we learn actually spring from our deepest interests – I think that’s true for most people, but it seems especially true for Autistic people. But sometimes our most passionate interests get used against us. Sometimes non-disabled people manipulate those interests to meet their own goals. There are behavioural therapists, educators and support workers who take away the things that autistic people love and make returning them contingent on “acceptable behaviour”. I think that’s cruel and misguided. The objects we hold dear, and the activities and issues we approach with laser-like intensity are not just interests, but are often also part of our attempts to learn about the world, about our bodies and our preferences, and often are powerful tools we use to help ourselves self-regulate. Taking them away because someone else has deemed them inappropriate or over the top is not just damaging, it’s counter-productive in every way. I can’t say enough about this!

NORM: Looking back, I see that despite your best efforts to fit in, your autistic self kept popping out – most dramatically through your art. Talk about that.

EMMA: Yes. My art has often been called over the top. It is quite byzantine! Lots of detail, lots of colour. For years I made these strange mirror/mask pieces.

They were self-portraits. I made masks of my own face out of plaster bandage. I painted them with multiple coats of gesso, sanded them until they were smooth. I added eyes made out of marble. I painted them with metallics and overlaid interesting caustic substances until they looked like ancient and weirdly mythic bronze sculptures. I embellished them with found objects, lichens, cloth. I glued them onto mirrors. Then I made casts of my own hands, palms forward, fingers splayed. I applied the same finishes to my cast hands.

I glued those hands onto the mirrors underneath the mask of my face, draped them with cheesecloth I’d dyed black and dipped in glue, and added lichens and twigs and leaves. The resulting image was startling, to say the least. There was me, transformed into a strange subterranean creature, mouth open, eyes wide, hands splayed – emerging from behind the glass through a sea of primordial sludge, or if you held the mirror over your head and looked up at it, maybe even descending face and hands forward from the sky like a disembodied, shocked Icarus. I made variations of this self portrait for years. Some were on mirrors, some were Druidic outdoor installations hanging from trees or in front of shards of mirror and glass.

What in the world was I trying to say? I wasn’t sure myself.

In retrospect, with Autism diagnosis in hand, I recognize that these images could look like the reproduction of a terrible stereotype – there she is, the Autistic person behind a glass wall, trying desperately to re-join polite society. It’s a terrible stereotype – Autism fundraisers use it to bolster their fear-mongering about what it means to be Autistic. The stereotype implies that we are cut off from others, that we live in “our own little worlds”, that we are as alien as the media leads the world to believe. Have I felt like an alien? Well, actually, yes. But even in my unconscious state, that was not exactly what I was trying to portray.

So what was it?

For the longest time, I didn’t know what I was trying to say, why these images were so important to me. But since I’ve come to understand what passing is, and that I’ve committed a huge part of my life to it, I’ve also come to understand why I have returned over and over again to that kind of self-portraiture. That’s me on the other side of the glass, trapped by my own internalized ableism. Trapped by the powerful narratives that I used to muscle and force myself into a constricted compliance with social norms. That’s me gasping for air, grabbing for freedom, desperate to let my true Autistic, stimmy self out into the open.

It’s been years since I made one of those mirrors (although I am making another one now). It’s taken me this long – through two diagnoses - ADD and Autism – to make sense of the imagery. Sometimes I could kick myself for having contorted myself into a facsimile of a socially accepted form for so long. But then I remember that empathy and compassion (two qualities we Autistics are thought to lack) also extends to self. I look at those images and my heart breaks and I want to be gentle with my earlier selves. And I remember a poem that helps me to integrate my past into my present so that I can invite the child, adolescent and young adult “me” back in without censure. The poet David Whyte writes:

“Hiding is a way of staying alive. Hiding is a way of holding ourselves until we are ready to come into the light. Even hiding the truth from ourselves can be a way to come to what we need in our own necessary time. Hiding is one of the brilliant and virtuoso practices of every part of the natural world. Hiding is underestimated.”

Hiding is a way of staying alive.

Hiding is a way of staying alive. This is deeply resonant. The act of hiding, or passing, is an act of self preservation. It’s something the younger me did with the kind of single-mindedness only an Autistic person can summon. It’s how I saved my own life for many years. The problem, though, is that it cannot be sustained. Passing is exhausting.

NORM: So let’s talk about your diagnosis. Because autism, like other disabilities, is stigmatized in our society, why would you choose to get a diagnosis? Isn’t that putting you in a stigmatized, devalued position?

EMMA: Glad you asked that question. It’s something that people have said to me before. After I received my first diagnosis of ADD, back in the late 1990’s, I once outed myself in a speech at a conference in California. The response was essentially negative – even among people I had known for years and whom I respected. They couldn’t figure out why I would want to self-identify with something they saw as devaluing and labelling. “We’ve worked so hard to eliminate labels. Why would you want to slap one on yourself?” I remember that experience because it was invalidating and painful.

And some people add that we should only “label jars not people”, which is a slogan in some circles. But I’m going to contest that idea for a couple of reasons. First, disability is not something to be ashamed of or hide. This is part of who I am. It has its upside and its downside, but it colours everything I experience in the world. So why try to hide it? The second reason is solidarity. Since I’ve figured out that I’m autistic, I have met the most amazing community of autistic adults. I am proud to be part of that community. It would feel fraudulent to me to pretend to be neurotypical, like I was letting down my community. Also, I’m at a position in life where I can use whatever influence I’ve gained to maybe change a few minds.

Now that said, diagnoses for children can be abysmally problematic, and can catapult them into an arsenal of therapies that I am glad I avoided. If it’s a medical diagnosis, for many children born today, it will be a gateway to a childhood of 40 hour therapy sessions and all the attendant messages that tell them they are broken and in need of fixing. The diagnosis in a sense can “implant” an identity of deficiency. And this is difficult to extricate themselves from as they grow older. Too many young adults who are the survivors of compliance-based therapy tell us that they experience long term PTSD from the very approaches that were supposed to be helpful.

So I am cautious in talking about how diagnosis worked for me. Because my diagnosis as an adult was categorically different than a medicalized diagnosis for a child. For me it was all about “aha” moments and the wonder of discovering that there were other people who shared my experience. The delight of discovering a community of belonging. Further, I had control over what I would do with that diagnosis, and how I would proceed

So here’s the difficult and nuanced part: a diagnosis can take you to a place where you no longer perceive yourself as broken, where you may have an opportunity to be introduced to a community of people who understand your experience because they also live it. So it can be positive. But when a diagnosis is something used against you to make you believe you are broken and in need of remediation, it can be a constricting force.

NORM: How do people generally respond when you tell them you’re autistic?

EMMA: I generally get one of two responses – “but you don’t look, seem, act autistic” or, (and this is my favourite), “well, that explains a few things”!

NORM: How do you respond when people say “but you don’t look/act/seem autistic”?

EMMA: Well, I can’t say I blame them for saying that! Until recently I didn’t even know I was Autistic! And like I said before, that’s because the ways in which autistic girls and women can show up often doesn’t look anything like the stereotypes the media gives us.

NORM: So supposing there was some magic pill that could “cure” you of autism, first, would you take it? And second, if you did decide on a cure, what would be gained and what would be lost?

EMMA: Well let’s get the first part out of the way. I wouldn’t take it. Now, as for what would be gained, I wouldn’t mind losing some of the things I experience that are often called co-morbids. I, like some other autistic people, prefer to call them co-occurring conditions. So, yes, you can take away my IBS and my anxiety and that would be just fine. But what would be lost relates to the question you asked me before this one. I’d lose my particular, idiosyncratic way of being in the world. As an autistic friend of ours once said when you asked him the same question “I wouldn’t want to be cured, because then I’d be ordinary!”

NORM: I know in my experience, there were multitudes of educators and physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists all trying to make me less disabled. I know this is also true for a lot of autistic individuals. Why do you think non-disabled parents and professionals get so concerned about suppressing autistic traits?

EMMA: You’ve often pointed out that the unintended consequence of all that therapy was to convince you that you were fundamentally broken, fundamentally less than. You’ve also talked about how it set you up to be at war with your disability, with your body, actually. When we first met, you gave a speech called “The Right to be Disabled”, in which you talked about your journey from that war into acceptance of your disability, and then how you became politicized and began to work on issues of disability rights.

I think parents get pulled into what I know you’ve sometimes called an “Armageddon” mindset. In other words, if I don’t force my child to do all this therapy, my child will never reach their full potential. It’s based on fear. Sometimes parents will defend some of the more damaging compliance based therapies by pointing to the fact that their child has learned more socially acceptable ways of being in the world. The question for me is always “at what cost”? Many adults who have experienced those therapies are not exactly grateful! In fact, there’s a lot of resentment out there. They often describe having PTSD as the result of having to override their natural coping strategies and mechanisms.

And when parents say – and they often do - “well, look, it actually worked for my child” I always wonder how they can be sure it was the therapy that worked, and not just normal maturation. After all, autism is a developmental disability, and that implies the capacity for growth and change. Because each autistic person is different, I think you’d have to split a person in two to really know if it was the therapy that worked or that it wouldn’t have happened anyway. One half of the person would be the control group with no therapy, and the other half would receive therapy. Since we can’t actually do that, I don’t think it’s ever possible to know how or why a person changes.

What we do know, though, is that teaching a person to suppress their innate traits and coping mechanisms is fundamentally damaging, because the unintended message is that you aren’t OK the way you are, and that you are in need of remediation and fixing. And again, removing coping and self-regulation strategies just because they don’t look “normal” is both counter-productive and cruel.

That said, there are therapies that are helpful – ways to work with people, not on them. Ways to help people learn the things they want to learn. A lot of autistic people – me included - say they could have used help navigating the social world, for example. But the best kind of help is supportive and individualized and non-coercive.

NORM: In my own life, going to my first disability rights conference and seeing other disabled people not only being proud about being disabled, but feeling completely entitled to ask for the support they legitimately needed was a changing point in my life. I know there were similar pivotal points in your life. Could you talk about them?

EMMA: Well, first of all, your speech, The Right to be Disabled was profoundly important for me. Of course I didn’t realize that it wasn’t just about other people, but was actually about me, too, until years later! And so many of the wonderful people in the disability rights sector like Catherine Frazeein her blog, Fragile and Wild and Dave Hingsburger's blog have had a huge impact on how I see and understand disability.

As you know, another powerful point was reading Laura Hershey’s incredible poem “You Get Proud by Practicing” . My introduction to the Neurodiversity Movement has been earth shaking. Nick Walker's blog ,Neurocosmopolitanism, and Lydia Brown's blog The Autistic Hoya and so many others. One particular event stands out in my mind, though, and that was meeting Kassiane Asasumasu (Time To Listen) a few years back. Kassianne was doing a talk for the disability centre at the University of Washington. The first thing I noticed was that the room was dimly lit with fairy lights – that was an immediate ahhhh. Then when Kassiane started talking, she calmly and matter of factly listed the accommodations she needed. And she enforced them! I was absolutely gob smacked! You mean you can ask for these things? I’d never given myself permission to do that. My life changed that day.

NORM: Up to the middle of the 1940’s, many clinicians and educators contended that all people with cerebral palsy had some degree of intellectual disability. In the last almost 80 years, we’ve come to understand that although some people with CP have intellectual disabilities, the two don’t necessarily go together. Could you talk about how that has played out for autistic people?

EMMA: Actually, I don’t think it’s been that long, even for people with Cerebral Palsy. I think it might have been the 1960’s. But to answer your question, the same is true for Autistic people. Some may have intellectual disabilities, some may not. In many ways, it’s not important. One of the things we reject in the Neurodiversity Paradigm is the notion of functioning labels. Just because someone can speak, it’s assumed that they are higher functioning. And when people can’t speak, it’s assumed that they have intellectual disabilities and are “lower functioning”. Many of my friends don’t use spoken words to communicate, but instead use AAC. Many are gifted writers, like Amy Sequenzia, Cal Montgomery and Sue Rubin . And besides, the whole notion of functioning is pretty subjective and episodic. Catch any of us on the wrong day, and we may look quite different than you expected.

Most of all, we want to always assume competence.

NORM: I know in the disability rights community, there can be a hierarchy between those with only physical disabilities - considering themselves superior to those with physical and intellectual disabilities? Is there a similar situation in the autistic community?

EMMA: Yes, and it’s really upsetting. If I have to hear “but my mind’s just fine” one more time... Now there’s another way this plays out. There are some parents of autistic children who reject the experiences of anyone who can speak, anyone they perceive as higher functioning. The way this often gets framed is “you’re not like my child” or “you’re just not autistic enough” and that is used to discount adult experiences. It’s a terrible double bind – if you can speak, you’re not autistic enough, and if you can’t speak you are discounted – this relates to what you and I have sometimes called the manipulation of similarities and differences. Other minority groups experience this terrible catch 22 as well. If you are struggling, you’re seen to be like every other person in your marginalized group – problematic and stigmatized and not credible. If you are doing well, then you must be the exception. This problem needs to be exposed and discussed and contested, because until it is, Autistic voices will continue to be silenced.

NORM: What would be people be surprised to hear about your experience of autism?

EMMA: When I am left to myself I am absurdly happy – and I always have been. Delving into the things I love best is a source of unmitigated joy and bliss. I am also very lucky. I am self employed and am able to have all the non-social downtime I need. You and I talk about engaging in parallel play, where we go off and do the things we need to do to, and get back together for a meal or a drink or to watch a movie on our own schedule. This is a lifestyle that is optimal for a lot of autistic people, and I don’t take it for granted. I have your support. People often think that because you have a physical disability that I must do much more of the support. This couldn’t be further from the truth. You support me in so many ways.

NORM: When we finished an interview with sensei Nick Walker, an autistic aikido instructor, educator, activist and writer, I jokingly said to him “I’ve never said this to another guy before, but thank you for explaining my wife to me”. It was in response to his comments about his intense and almost ecstatic appreciation of beauty. Could you elaborate on this?

EMMA: Haha! Yes. I experience huge visceral reactions to beauty. Light, colour, movement, art etc. I’m often amazed by the mediocre responses some neurotypical people have to things that fill me with ecstasy. Much of it is visual, but not all of it. I respond to words with bliss, and I really get into the zone with cooking. Anagrams and crossword puzzles are ridiculously wonderful things to me! Nature, animals. It goes on. It never gets old.

NORM: So finally, what are two or three things that you might suggest to support workers, parents and educators as they support autistic individuals?

EMMA: I would suggest they watch the video of the interview you had with Nick Walker. In that interview, you and Nick talked about "Trusting the Weirdness." Let autistic people relate to the world in their own unique ways. Another thing that’s been helpful to me and to some other autistic people I know is movement. Many of us require an inordinate amount of movement on a daily basis to help us self regulate. Also to help us gain spatial awareness. I’ve never been particularly good at sports or anything like that – it’s hard for me to know where my body is in space. But things like swimming, running, hiking, and even dancing (though I’ve never been particularly good at that, either!) have been helpful. Mostly things I can do by myself. Body awareness is something I’ve always had to work at. Most of the time I sit with a pillow on my lap, something I’ve always done, and often seems strange to some people. But this is something that I did well before I knew I’m Autistic, and it’s always been helpful in keeping myself located in space. These days I have a weighted blanket that I use primarily to regulate myself before I go to sleep. Physical activity has always been very important to me, even though I retain a complete inability to understand the rules of any sports like soccer or hockey or basketball!

Probably the most important thing I’d say is – introduce people to other Autistic adults in the neurodiversity community! It doesn’t matter if you don’t know anyone locally right away. Go on line. Find the blogs, find the people who are autism positive and creating alternative narratives. This is a vibrant community full of people only too happy to help. Look at some of these blogs, for example… www.30daysofautism, There are many more, but Leah Kelley’s blog will lead you to all the best of them (she has them listed on the right hand side of the page).

And finally, if there was any advice I’d leave parents, educators and support workers with, it would be this. I would reiterate something that PACLA (Parenting Autistic Children with Love and Acceptance) says best (we have it in our kitchen on a fridge magnet) – Don’t change your autistic child, change the world! And I’d add Leah Kelley’s brilliant piece on practicing acceptance (which we also have on our fridge)!

And look at Lei Wiley-Mydske’s blog. It’s wonderful. Especially check out the neurodivergent narwhals